Understanding Inflammaging: How Inflammation Affects Brain Health as You Age

As we age, the brain and body undergo changes that bring about new health considerations. Some of these shifts are inevitable as your body’s ability to perform its numerous functions gradually declines. One such change is known as inflammaging.

What is inflammaging? Inflammaging, by definition, is chronic inflammation that naturally occurs as a result of aging—hence the combination of “inflammation” and “aging.” The term was first coined by researchers in a study published by the New York Academy of Sciences and has received a great deal of attention from the medical and research communities in recent decades.

Understanding and addressing this age-related chronic inflammation is one of the most important steps you can take toward healthy aging.

Acute Inflammation vs. Chronic Inflammaging

Acute inflammation, the kind that produces redness, swelling, and pain following an injury, is an adaptive response and generally doesn’t lead to further issues. It’s chronic inflammation, such as inflammaging, that concerns scientists and doctors.

What Is Chronic Inflammation?

Chronic inflammation is an example of what happens when a beneficial and adaptive system goes off the rails. Inflammation is a normal function of our immune system, meant to protect us and aid healing. Once it receives a signal, the immune system sends pro-inflammatory proteins called cytokines to an injured or infected area. This makes blood vessels more permeable to allow fluids and immune cells to move into and heal damaged tissue.

Most of the time, the immune system is called in when there’s a job to do and stands down once healing has completed, posing no threat to the body. Sometimes, however, the immune response doesn’t fully “shut down,” which means wayward immune cells can wreak havoc on the body and brain.

Chronic inflammation has been suspected as the mechanism driving a number of chronic diseases, including:

- Diabetes

- Cardiovascular disease (CVD)

- Arthritis and other joint diseases

- Allergies

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Psoriasis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

However, no area of the body is exempt because chronic inflammation is systemic inflammation. Even the brain, with its highly selective blood-brain barrier to keep out toxins, is susceptible to inflammation. Chronic inflammation, including inflammaging, “may contribute to neuronal damage” and has been implicated in the following neurodegenerative diseases:

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Parkinson’s disease

- Neurotropic viral infections

- Stroke

- Paraneoplastic disorders

- Traumatic brain injury

- Multiple sclerosis

Neuroinflammation has also been associated with psychiatric and mood disorders, such as schizophrenia, depression, anxiety, and PTSD.

A Closer Look at the Cycle of Inflammation

To understand the mechanism behind inflammation, let’s look at a little chemistry.

The Impact of Reactive Oxygen Species

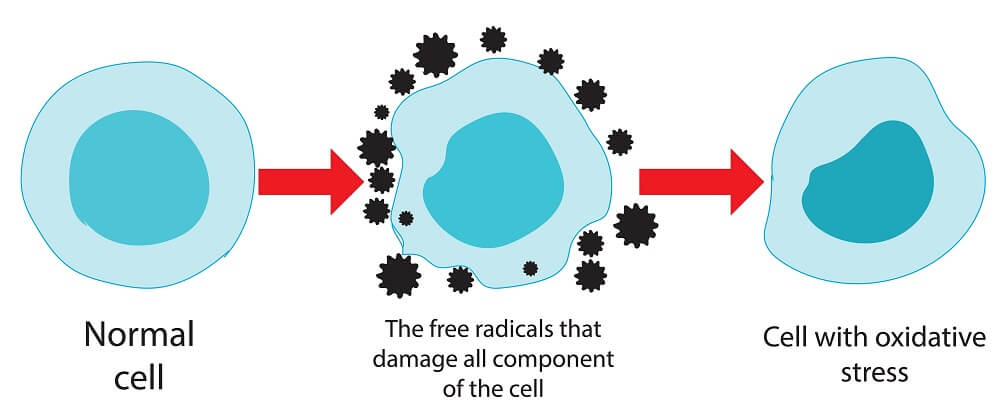

Chemical compounds are neutral or stable if all their electrons are paired up. When an electron is unpaired, it becomes extremely reactive because it seeks another electron to pair with. These highly reactive compounds with unpaired electrons are called free radicals. Often containing oxygen, they’re also referred to as reactive oxygen species (ROS).

While most chemical reactions are relatively controlled within the body, free radicals are like ricocheting bullets—they attack their surroundings violently and randomly.

Desperate to find a partner for their lonely electron, free radicals will steal an electron from any nearby molecule—including your DNA and other important parts of the cell. This process is called oxidative stress.

While this may sound bad, your body usually has it under control. Even though oxidative stress used to be seen as harmful, an adaptive function “has been gradually acknowledged over the last four decades”—ROS are produced all the time because they’re needed for important processes like tissue repair and embryonic development.

So why are we told that ROS or free radicals are so bad for us?

The Body’s Responses to Free Radicals

Our bodies learned to handle a certain amount of oxidative stress by developing “antioxidative machinery” to neutralize ROS and free radicals. Enzymes and antioxidant molecules (such as vitamin C or E) can break down these potentially harmful molecules before they cause damage.

However, these two systems need to stay in balance. If you have too many ROS and not enough antioxidants, ROS will build up, leading to conditions like neurodegenerative diseases, atherosclerosis, cancer, and others.

How Inflammation Affects the Brain

Unlike acute inflammation from an injury, chronic inflammation tends to affect the entire body, including the brain.

If you’ve ever had the flu or a cold, you’ve probably experienced the kind of brain fog that systemic inflammation can cause, even if it’s only temporary.

Long-Term Impact of Chronic Inflammation on the Brain

According to a 2015 review, the same processes that create temporary cognitive impairment with a cold can cause severe or even permanent brain damage if inflammation sticks around long-term.

They note that in situations where a chronic infection goes unnoticed for a long period of time, such as in the case of hepatitis C, patients show “increased rates of fatigue and depression, as well as evidence of metabolic brain dysfunction.”

The review describes how the nervous system and the immune system interact. When there’s chronic inflammation, it releases pro-inflammatory cytokines and other immune

mediators into the bloodstream.

These can then reach the central nervous system (CNS) and even cross the blood-brain barrier, a semipermeable barrier that keeps many harmful molecules out of the brain, where they can affect “neuronal and glial well-being.” This can trigger a cascade of harmful outcomes, from inflammation of brain tissue to disturbances in normal brain function.

Changes in the Way the Brain Works

Systemic inflammation can cause cognitive impairment through mechanisms that create “profound structural and functional changes” in the brain, including:

- Interfering with nutrient flow to the brain

- Leading to an “energy crisis” in the brain

- Reducing functional connectivity

- Aging the brain through mitochondrial damage and oxidative stress

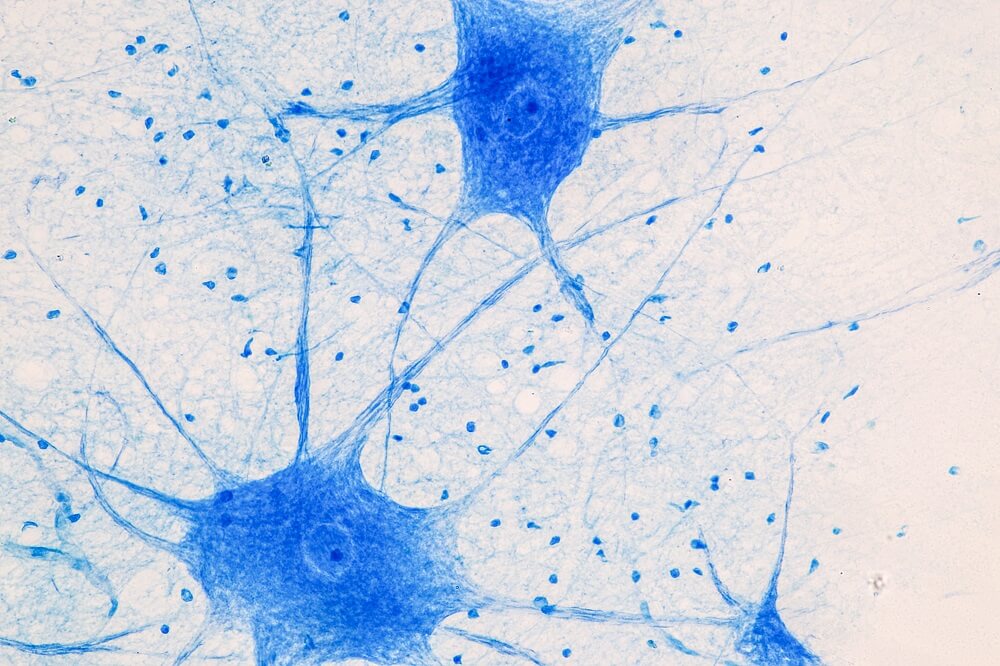

Research shows “the main cause of brain aging appears to be neuroinflammation via aged brain cells and a weakened immune system.” Neurons, which are responsible for transporting information, and glial cells, which help protect neurons, are especially vulnerable to the harmful effects of inflammation in the brain.

The cumulative effects of these processes are a major driving force behind not only age-related decline but also the development of various neurodegenerative diseases.

The Impact of Inflammaging on Neurodegenerative Diseases

As our understanding of inflammaging grows, so does our grasp of its full effects. Chronic inflammation can play a major role in the development of brain diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s:

- In Alzheimer’s disease, inflammation seems to interfere with the brain’s ability to clear out abnormal proteins that build up and damage brain cells. It also disrupts communication between neurons in the brain.

- In Parkinson’s disease, lasting inflammation contributes to the death of the brain cells that produce dopamine, a chemical that helps control movement. This can lead to symptoms like tremors and difficulty moving.

The link between inflammaging and neurodegeneration sheds light on the progression of age-related diseases. Science shows that inflammaging “is a determinant of the speed of the aging process and of lifespan.”

Controlling this inflammatory response is an important aspect of potentially treating these diseases and, ultimately, preventing inflammaging’s harmful effects on the aging brain.

The Role of the Gut in Brain Health

The concept of gut health has been everywhere lately as research into the topic has increased exponentially in the last decade, and so far it’s looking interesting.

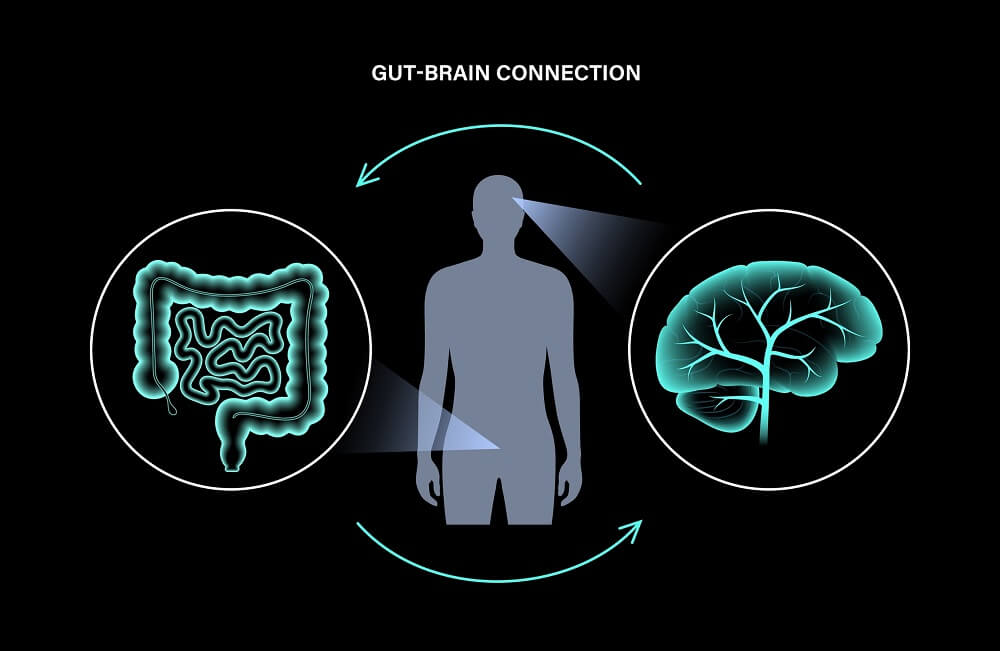

Your gut microbiome, or the trillions of microorganisms colonizing your entire digestive tract, is a critical player in your overall health but especially your brain health. Scientists now recognize the gut-brain axis (GBA), a two-way pathway that links the gut and the brain.

A key physical pathway is the vagus nerve, which connects the brain to the gut through the enteric nervous system—sometimes called the “second brain” because of the multitude of neurons in the digestive tract. Up to 95% of the body’s serotonin, a neurotransmitter that influences your mood, is also produced in the gut.

With this connection, it’s no surprise that gut health has been linked to a host of neurodegenerative and psychiatric conditions.

The Gut-Brain Axis and Inflammaging

More than just physical sensations can be transmitted via the GBA. Byproducts of the microbes in your gut—”bacterial toxins” in this case—have also been found to travel to the brain and cross the blood-brain barrier. This allows the chronic, low-grade inflammation often seen in inflammaging to take hold in the brain itself, where it can slowly build.

Gut-brain crosstalk can also be affected by the immune system. An overactive immune response can increase the permeability of the BBB, allowing more unwanted outsiders into the brain environment. The “leaky gut” phenomenon may also lead to a “leaky” blood-brain barrier.

Researchers are exploring how promoting a healthy gut microbiome could reduce inflammaging to help slow brain degeneration, meaning gut health may be critical to protecting brain health as you age.

Learn More About How Food Drives Chronic Inflammation

Anti-Inflammaging Strategies: What Helps?

Studies have shown that chronic stress and the modern lifestyle are major drivers of low-level system inflammation. Remember that the body has stress as well as anti-stress cellular machinery; as our modern lifestyles tend to accelerate the stress system, we need to engage the anti-stress system to keep it in balance. This can make for a powerful anti-inflammaging strategy.

Here are some ways you can ramp up the anti-stress machinery.

Diet

Humans have been around for about 300,000 years, and for 99.5% of that time, our diet looked considerably different than it does today—in short, we didn’t evolve for constant fried, refined, and processed food. Focus on real food and ample fruits and veggies for antioxidants, and you’ll be on your way toward fueling the anti-stress system.

Exercise

Staying physically active has been shown to reduce levels of chronic inflammation. One study showed that just 20 minutes of exercise at a moderate level was enough to reduce low-level inflammation; another found that “cycling exercise, multimodal, and resistance training effectively decreased pro-inflammatory cytokines.”

Stress Reduction

Of course, finding ways to reduce stress in life isn’t as easy as snapping your fingers—but it can be done, and it’s a process worth starting. Studies have shown that inflammation and mental health disorders “are closely intertwined, and possibly powering each other in a bidirectional loop.” Essentially, persistent low-level stress can put you at risk for inflammation as well as mental health problems.

Prioritize Brain Health with Targeted Inflammaging Solutions

Brain health is intricately linked to our overall health and fitness. If you want to keep your brain fit and healthy for as long as possible, maintaining a healthy lifestyle full of lots of real food and healthy movement is a great place to start. From there, targeted treatments can offer additional ways to improve brain and body performance as you age.

The Aviv Medical Program uses non-invasive hyperbaric oxygen therapy and creates a personalized plan for each client that combines cognitive and physical training, plus nutrition coaching, to achieve optimal results. Based on over a decade of research and development, the intensive treatment protocol is customized to your needs, with amazing potential to address the biomarkers of aging.

Aviv Clinics in central Florida is the only center in the United States to offer this program. Learn more about reversing the biology of aging.

Aviv Medical Program provides you with a unique opportunity to invest in your health while you age