What Is the Gut-Brain Connection? Exploring Gut Health and Brain Function

With much information available about “gut health” these days, it is difficult to know what’s real and what’s just hype. Data emerging from recent scientific research strongly suggests that gut health matters – much more than we previously thought, thanks to the gut-brain connection. The trillions of microbes that live in your gut may play a key role in keeping you healthy. Some scientists now treat the gut microbiome like an organ system, as important as our respiratory or circulatory systems.

Gut flora works in symbiosis with other organ systems, which means the gut could impact – and even prevent – numerous diseases and conditions. Autoimmune disorders, Alzheimer’s, heart disease, cancer, and even depression have all been associated with gut health.

For this reason, innovative centers such as Aviv Clinics are using customized nutrition plans as an integral part of treatment for clients seeking to improve their cognitive and physical performance, or symptoms of conditions like fibromyalgia, Lyme, dementia, and traumatic brain injuries.

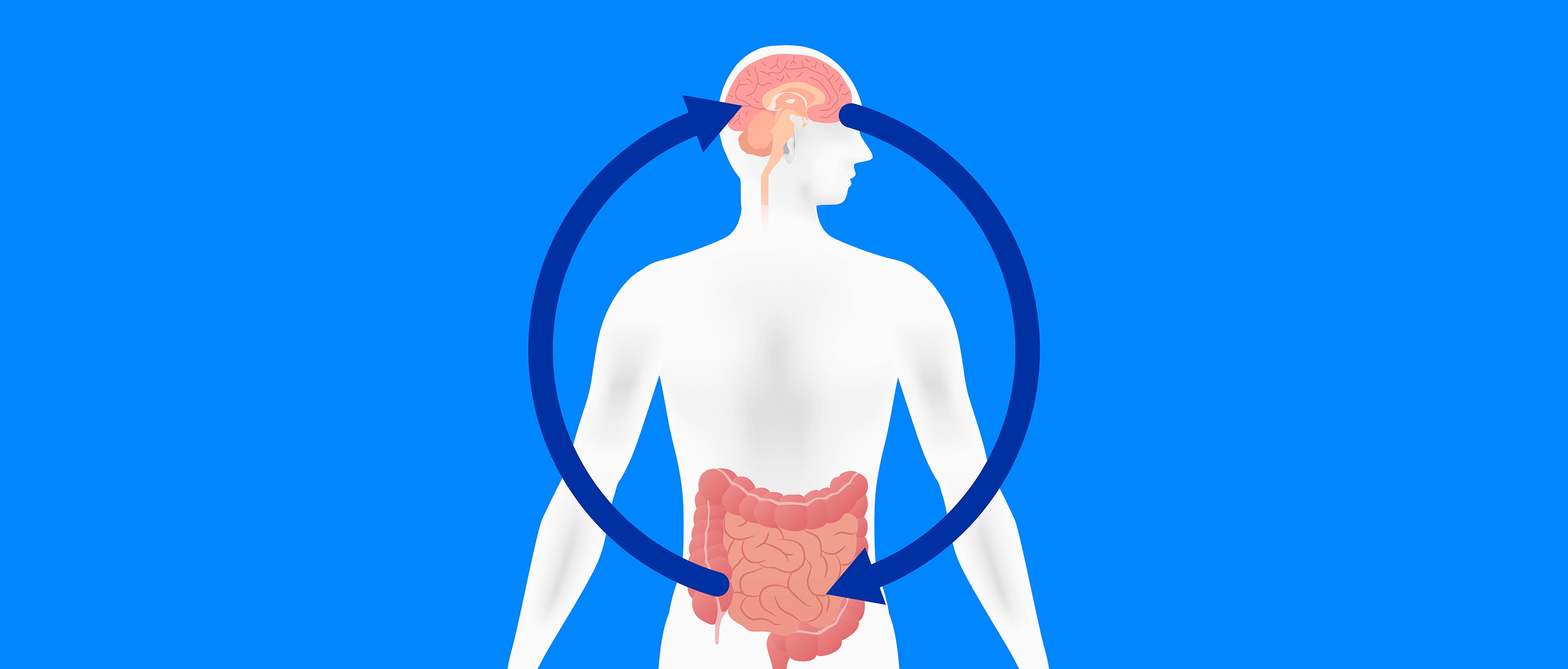

Why Gut Health Matters for Brain Health: The Gut‑Brain Connection

As scientists continue to study our complex brains, we are learning that the brain’s functions extend far beyond the skull. The brain is deeply connected to the entire body, especially the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, or the “gut.” We can’t talk about brain health or brain function without including gut health and function. It’s exciting news for anyone struggling with neurological or psychological disorders. Could the secrets behind mysterious, complex, or debilitating conditions reveal themselves in the gut?

So what is going on in the gut, and how does it affect our health?

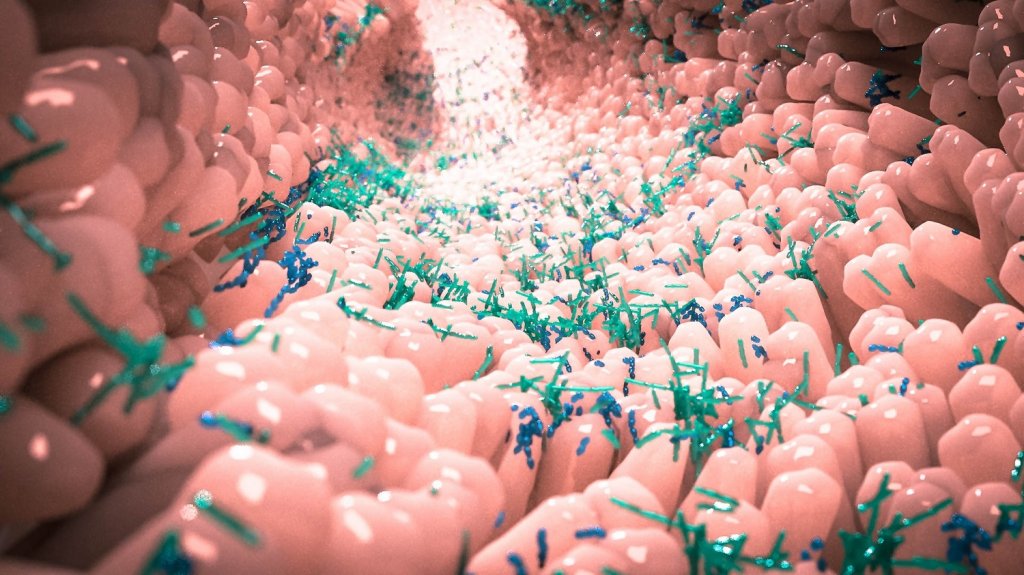

Understanding Your Microbiome: A Key to Better Gut Health

Your gut is home to over 100 trillion microbes, collectively called the microbiome or gut flora. With more than 1000 species of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa in your gut flora, they outnumber your human cells by 10 to 1.

Each microorganism in your body also contains DNA; added up, the microbiome contains roughly 200 times the amount of genetic material as in our own human cells. In fact, according to the University of Washington, “autoimmune diseases appear to be passed in families not by DNA inheritance, but by inheriting the family’s microbiome.”

The GI tract (via the mouth) is an entry point into the body, and the microbiome helps to keep out invaders by maintaining the intestinal barrier. This barrier acts as a filter to let in nutrients and keep out pathogens. The intestinal barrier also helps us digest our food, providing nutrients we’d otherwise be unable to harvest.

Gut Health Basics: Good vs. Bad Microbes Explained

The thought of trillions of bacteria hanging out in your body may seem a bit disarming. Generally, though, our guts are inhabited by commensal (good) bacteria and other microbes. Most microbes are harmless, so it’s important to understand that calling some microbes “good” and others “bad” is an oversimplification. Even the ones that may cause harm don’t always do so. A specific species of microbe might be completely harmless under most conditions, but potentially cause disease under different conditions. In the GI tract of an otherwise healthy person, the potentially harmful microbes reside in small numbers and are typically kept in check by other microbes.

What Makes a Healthy Gut?

Science can’t answer this definitively because everyone’s microbiome is unique. It’s not about one species of microbe or even a certain combination; what a healthy gut looks like varies from person to person.

“It would be great if we could identify 10 or so bacteria and say these are the ones you need most, but it doesn’t work that way, and there is no magic bullet,” says Dr. Elizabeth Hoffman, an infectious disease doctor from Massachusetts General Hospital.

What healthy guts have in common is diversity. They are colonized by a wide variety of microbial species. Assessing the health of the microbiome is about the balance and stability in the entire “ecosystem” of the gut. When this balance is thrown off, the microbiome can shift into a state of dysbiosis, where its normal supportive functions in the body get disrupted. As a result, the body becomes even more susceptible to disease and dysregulation.

What Causes Gut Dysbiosis?

Many factors have been found to cause gut dysbiosis: environmental factors like stress, diet, medications such as antibiotics, illness or disease, or even “inflamm-aging” can throw off the balance. Neurological and psychological conditions are being associated more and more with gut dysbiosis. By understanding the physical and functional links between the brain and the gut, we can see how their fates seem to be intertwined.

Your ‘Second Brain’: How Gut Health Influences Neurological Conditions

The sensation of butterflies in your stomach is one example of the gut-brain connection. If you’ve had digestive issues in stressful times, it’s not just a coincidence. Our thoughts and feelings can influence our health by directly altering the gut. Neurons, which we typically think of as only residing in the brain, also line our gastrointestinal tract and branch into our stomach and intestines. With over 500 million neurons, the enteric nervous system (ENS) is sometimes referred to as the “little brain” in our gut. This neural matter doesn’t contribute to thinking or consciousness, but it is part of a robust pathway for two-way communication between the big brain in your skull and your microbiome, known as the Gut-Brain Axis (GBA).

The Gut-Brain Axis is a complex two-way communication channel between the brain and the gut, involving the limbic system, central nervous system (CNS), autonomic nervous system (ANS, our fight or flight system), ENS, immune system, hormones, and more. Whatever is going on in your head, including emotions, behavior, and even thoughts, could partially be affected by what’s going on in your gut, and vice versa. As a result, if we want to understand neurological conditions, we can’t just study the brain. The gut microbiome has been linked to Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s, depression, anxiety, and even “motivation and higher cognitive functions” all have been linked to the gut microbiome. The gut microbiome presents an area for more research that may be the key to treating these disabling conditions.

How Gut Health Drives Brain Chemistry Via the Gut‑Brain Axis

One of the gut’s primary roles is the production and turnover of neurotransmitters like serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine. The gut produces up to 95% of serotonin, sometimes called the “happiness hormone,” in our bodies. The gut also maintains the integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier. This protective layer acts as a filter to keep out bad pathogens and toxins while letting in nutrients. If this barrier gets disrupted, invaders can infiltrate the body, promote inflammation, and exacerbate many autoimmune disorders. Gut flora also produces a metabolite called short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) that are integral in gut-brain signaling. When this signaling malfunctions, it can contribute to nervous system disorders, ranging from neurodevelopmental disorders to neurodegenerative diseases.

Brain‑to‑Gut Influence: Stress, Hormones & Gut Health Feedback

The microbes in our gut have receptors on their surface designed to interact with the neurotransmitters produced in the brain. Stress can directly affect your neurotransmitters, which can go on to influence the gut flora and its habitat. Stress can also change the total mass of the microbiota and the composition of species in the gut.

The GBA may control and respond to stress through our hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis, which involves hormones like cortisol. One theory of depression is that overactivation of the HPA axis often causes heightened levels of cortisol. The brain can also affect the gut by changing the habitat for the microbiome. This includes mucosal secretions in the intestines, altering how fast your bowels move, and other environmental conditions. It can also directly affect what enters your body from the outside and your immune function.

Tips for Better Gut Health to Support Your Gut‑Brain Connection

Here are a few tips:

Diet: It’s all about diversity. Eat a wide variety of foods for a healthier microbiome.

Stress: Keep your stress in check. When you’re stressed, your microbiome is stressed.

Antibiotics: While useful for fighting infections from harmful bacteria, antibiotics also often kill some of the good bacteria in your gut. Use of antibiotics may contribute to dysbiosis.

Prebiotics and Probiotics: Probiotics and prebiotics work together. Probiotics contain good bacteria that could correct gut dysbiosis. Probiotics may also improve depression and anxiety after just 30 days. Prebiotics are healthful carbohydrates and fiber from fruits and vegetables that help feed your probiotics. The more colorful your diet, the healthier your diet — and your gut — are likely to be.

The Bottom Line: Why Gut Health Is Vital for Brain & Whole‑Body Wellness

The discovery of the Gut-Brain Axis tells us that your thoughts, feelings, experiences, and environment all play into gut health, and can directly impact your overall health.

Aviv Clinics delivers a highly effective, science-based treatment protocol to enhance brain performance and improve the cognitive and physical symptoms of conditions such as traumatic brain injuries, fibromyalgia, Lyme disease, stroke, and mild cognitive impairment. The Aviv Medical Program is customized to each client’s needs and goals. The program can include nutritional support in addition to a unique hyperbaric oxygen therapy protocol. The personalized Aviv Medical Program and our HBOT protocol are based on nearly two decades of research and development.

Contact us to learn more.

Last update: June 25, 2025

Aviv Medical Program provides you with a unique opportunity to invest in your health while you age.